I expect all of the following:

The vast majority of work1 currently performed by flesh and blood humans2 in our world will eventually be turned over to much more productive machines.

It will be possible to build machines that are shaped like the kinds of agents that ordinary folk psychology3 describes, i.e. “agent-shaped” machines.

In the long run, most of the work performed by machines will be handled by ones that are not “agent-shaped”.

Why do I expect #3, in light of #1 and #2? If it will be possible to build “agent-shaped” machines, and if it will be cost-effective to use such machines as substitutes for human employees, then why wouldn’t we mostly just do that?

Let me be more specific. By “agent-shaped”4, I have in mind machines embodied in form factors similar to human individuals at least in terms of a few specific features:

It has a single, persistent thread of experience.

It acts according to its own internally-represented beliefs and preferences.

It would be capable of operating autonomously, if it so chose.

The key consideration here is not just whether “agent-shaped” machines will be substantially more productive than human workers, but rather whether they will beat out other attainable system designs that might be even more productive by virtue of dropping this “agent-shape”. If they do have these features, it will likely be either because they serve some particular function better than rival designs, or because they previously did but are not pruned away for one reason or another. To get a flavor for the space of alternatives, we can consider known examples of natural and artificial systems that lack at least one of the above features.

Some machines are reset between uses because they serve time-limited functions, rely on starting from a predictable initial state, or otherwise do not benefit from persistence. Computer programs intended for persistence are often designed to do so in a way that isolates the effects of different invocations of the program.5 The ease of making copies of a program and communicating between them opens up possibilities that go beyond the “single thread” pattern. For example, it is possible to have many copies running in parallel and to then leverage their collective work without necessarily reconciling their threads of experience into a linear order.6 Likewise, instances can be modified at runtime. This allows for the deletion of existing memories or the insertion of non-veridical memories, breaking linear persistence.

Moving to the “acts according to its own internally-represented beliefs and preferences” feature, powered machinery like tractors are clear examples of systems that are productive in part because the removal of this feature brings added controllability and predictability, in comparison to the animal-powered systems they replaced. Moreover, law firms, PR consultants, and other service businesses inhabit economic niches that incentivize them somewhat to act according to the beliefs and preferences of their clients, to serve those clients best interests.7 If analogous structures hold across large fractions of future work, that work may be handled by systems that do not act primarily according to their own internally-represented beliefs and preferences (though maybe under the control of others that do).

Lastly, we know of many effective systems where individual instances are not “capable of operating autonomously”. Viruses are a natural example of this, as a class of replicators that thrives in a manner dependent on hosts. Within human culture, corporations and other organizational forms have certain “agent-shape” features (like internally-represented beliefs and preferences) but remain dependent on other agents at different scales to carry out their work and maintain themselves. Similarly, in eusocial and obligate social animals we see a kind of interdependence where the survival and productivity of any one instance requires the support of a larger group.

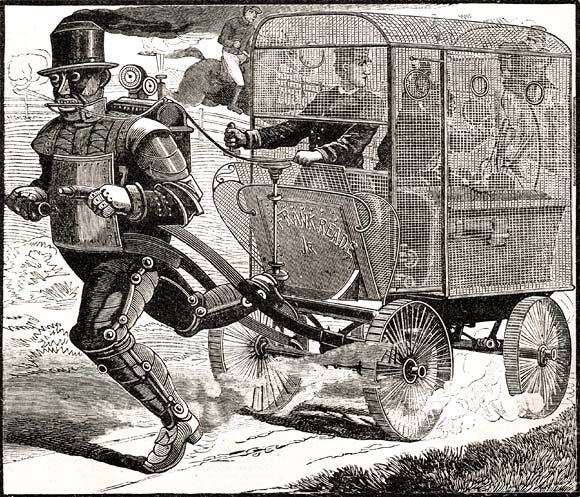

It is conceivable that “agent-shaped” designs could end up favored, even taking into account the space of alternatives. In the strongest case, this form factor might be generally optimal in some way. If there are other competitive designs, it may still be that future environments will have little variation or weak selection pressures, such that “agent-shape” traits get locked in for accidental reasons. But beyond these general factors, there is at least one specific factor that could allow “agent-shaped” machines to win out in certain areas. For tasks where there is a user who needs to interact with a system and where it would be costly to train them on it, providing them with affordances in a familiar shape—a kind of skeuomorphism—could be advantageous. Shaping machines to behave like agents for the benefit of their users seems like a reasonable and competitive near term8 strategy for those tasks. It is unclear, though, to what fraction of automatable labor this will apply in the long run.

Whether measured in terms of joules, or operations per second, or tasks, or share of income, or any other reasonable comparative measure of work.

If there are humans that are no longer flesh and blood, because they have turned digital in some form or another (link), they count as machines for the purposes of this post.

“Folk psychology” here just means the set of abstractions that we normally use when reasoning about and talking about the causes of human behavior (link). For example, it includes the assumption that our behavior is steered by internal states (like beliefs and desires) that others cannot directly inspect and modify.

Note that I am specifically not asserting that machines will lack the competencies typically associated with agents, such as being able to take actions or form coherent plans. The discussion here is only of the form factors we should expect them to have.

If this is of interest to you, Robin Hanson’s book Age of Em (link) further explores some of the potential social and economic consequences of having digital mind emulations that are amenable to this kind of deployment.

In the short term, users may have trouble with a new interaction paradigm. But if they are repeatedly exposed to it, they may adapt to it and no longer need the same supports. An example of this is visible in the transition from skeuomorphic design to flat design as users became accustomed to computer interfaces (link).